Identifying the Verticals and Metrics That Contribute to Sustained Success in High Performance Sport

- mindflowperformance

- Jun 6, 2020

- 31 min read

Introduction

For an organisation to achieve long term and sustainable development, it must consider economic, environmental, cultural and social factors (Waśkowski, 2015). Beyond development, defining and measuring success in HPSOs is a complex exercise, exacerbated by the fact that such institutions do not exist in isolation from their matrix of stakeholders, each presenting with different needs (Bof, 2006).

Stakeholders

Stakeholder theory acknowledges that there are many entities interested in how, and with what result, a business functions (Friedman & Miles, 2002). Stakeholders are people or groups, organisations, institutions or commercial entities, which have a legitimate interest in the activities of an enterprise in pursuit of its goals. These may also influence the enterprise or be influenced by the enterprise (Clarkson, 1995). In the sports setting, stakeholder attitudes and actions can influence the success of the team, although the nature of involvement and expectations will vary for each stakeholder. Consequently, a sports organisation has to apply various strategies that address each specific collaboration.

In professional soccer, twelve potential stakeholders have been identified as contributing to a two-way relationship with a team’s brand (Brand Finance, 2019). Internal stakeholders are identified as: players; directors, technical staff; all other employees. External stakeholders are specified as: debt providers; investors; sponsorship partners; merchandising channels; broadcast and media; existing customers; potential customers; and fans.

However, other stakeholders should also be considered, including competitors, international and national sports governing bodies (e.g. FIFA, International Olympic Committee [IOC], UK Sport), unions (e.g. Professional Footballers’ Association, National Football League Players’ Association), league administrators (e.g. English Premier League [EPL], National Basketball Association [NBA]), government authorities (e.g. environmental agencies, tax agencies, local councils, police forces, transport providers), service providers (e.g. private security companies, catering providers), geographical neighbours and lobby groups (e.g. environmental protection groups, community action groups).

Identification of Verticals That Contribute to Success in HPSOs

The relationship between the outcome of participation in the arena of play, the financial health and the interactions with the communities that the organisation impacts, ensure that defining success demands the consideration of factors beyond the results of the team, despite this being the most visible representation of the organization (Bof, 2006). In his introduction to the Annual Report 2017-2018, FC Barcelona President, Josep Maria Bartomeu i Floreta highlights the multi-faceted forms of success that define his organization, summarising that “This is the Barça that is improving society through the positive impact of sport, social commitment, research, innovation and training. For members of our Club, what counts is that our teams win championships, and what also counts is everything that sets us apart from the rest, and defines our identity” (FC Barcelona, 2018).

The report (FC Barcelona, 2018) itself gives a thorough performance review of:

1) Professional sports teams - sports team performances including soccer, handball and basketball; becoming a sporting reference point; building relationships with sports institutions;

2) Knowledge - youth and post-graduate education, social awareness, Barcelona Innovation Hub, conferences, service training programmes, life skill workshops, technology, research development and dissemination;

3) Social - member participation in the club, fan clubs, amateur sports, social impact foundation projects and building relationships with non-sports institutions, alumni;

4) Barça Brand - brand development, and positioning, fan zones, museum, revenue diversification and revenue internationalisation, public relations, international and diplomatic relations, media;

5) Global Business - sponsors, merchandising, global youth academies, tours, exhibition games;

6) Heritage - development of extended urban area around stadium (Espai Barça), innovation hub;

7) Support - supporting department activity e.g. Human Resources, Operations, Travel, Planning Strategy & Innovation, Systems & Technology, Access & Accreditations, Compliance and Legal;

8) Economic Report - debt management, payroll management, operational efficiency, innovation, digitisation, accounting and governance.

Each sector’s performance, totalling in excess of 400 actions, is measured in reference to the strategic projects and related strategic targets, which together comprise an extension to the strategic plan commissioned in 2015. The plan was compiled to provide a six year roadmap, overseeing the mandate put in place in line with the vision of “transforming the world through sporting excellence” and the mission, “to become the most admired, loved and global sports institution in the world” (FC Barcelona, 2015). It is apparent, therefore, that on-field success is critical but just one element defined in the lines of strategy identified in this document. Comprehensive reports are outlining similar scopes of involvement from other HPSOs such as Real Madrid, Borussia Dortmund, Juventus and City Football Group (Borussia Dortmund, 2019; City Football Group, 2019; Juventus, 2019b; Real Madrid, 2019a, 2019b).

Whilst cases such as FC Barcelona, Real Madrid, Juventus, Borussia Dortmund and City Football Group demonstrate an expansive list of criteria against which success may be measured, some elements are only appropriate given the sporting status, global reach of the brand and financial power of these organisations (Borussia Dortmund, 2019; City Football Group, 2019; FC Barcelona, 2019; Juventus, 2019b; Real Madrid, 2019b). However, the overall performance areas identified in the annual reports of such organisations are a useful framework upon which to deconstruct the assessment of success in all HPSOs (Hatum & Silvestri, 2015).

Key Performance Indicators and Objective Performance Metrics

In order to objectively ascertain whether individual criteria are being met and to what extent, key performance indicators (KPIs) must be established using valid and reliable measures, indicators and metrics. A meaningful performance indicator is a quantification that provides objective evidence of the degree to which a performance result is occurring over time (Barr, 2017). To this extent, KPIs will evolve as people, departments and organisations develop or change focus.

KPIs should be related to the measurable goals that have been set, as opposed to looking for things to measure in order to compile a battery of KPIs. Additionally, each stakeholder should be engaged in setting relevant KPIs to which their contribution will be held accountable, otherwise they are likely to be deemed irrelevant and ignored. Whilst setting meaningful KPIs can be challenging, especially if feasible data is hard to identify, Hubbard states, “if something is better, then it must be observable or detectable. And if it’s observable or detectable, it can be counted in some way. And if it’s counted, it’s measurable”(Hubbard, 2014).

Sports Teams

At a first-team level, the nature of sport and in particular soccer, is that the results on the pitch will always be the paramount concern for all involved at the club (Ward et al., 2013). Meanwhile, in American sports franchises operating in competitions such as the National Football League (NFL), where there are no development or youth teams, these results are likely to hold even greater relevance throughout the organisation. Consequently, league tables, play-off appearances, promotions, relegations and championships are easy reference points for success.

Within game analytics can be used to define success through key player performance metrics for each position, which can be aligned with the philosophy, style and systems that a team chooses to adopt. For example, in soccer, these may include goals scored, goals conceded, total shot attempts on goal (on and off target), ratio of the sum of goals scored/assists/shots on target:total shots, total shots on target, total assists, total crosses made, total crosses completed, total passes completed, total dribbles, total dribbles completed, total tackles made, total tackles won, total blocks/clearances/interceptions, yellow cards received, red cards received, total fouls committed, total shots on goal by opposition team, ratio of goals conceded:goalkeeper saves, total saves made by goalkeeper (Carmichael et al., 2011).

Each sport and specific league will be able to identify unique combinations of factors that are statistically related to success in their own individual environment (Mora, 2018; Watson et al., 2017). For example, a recent study in Chinese Super League soccer reported significant physical performance differences between groups, as identified for sprinting (top-ranked group vs. upper-middle-ranked group) and total distance covered without possession (upper and upper-middle-ranked groups and lower-ranked group).

In relation to technical performance, teams in the top-ranked group exhibited a significantly greater amount of possession in their opponent’s half, number of entry passes in the final third of the field and the penalty area, and 50–50 challenges than lower-ranked teams, whilst time of possession increased the probability of a win compared with a draw (Yang et al., 2018). However, given the sport is at a different stage of evolution in this specific league compared to other soccer leagues, for example the EPL, using the same markers to ascertain a successful outcome in other leagues might not be relevant.

Within season analytics can be used to define success through key team performance metrics such as points won, points won during current season as a percentage share of total points won by all clubs in current season/previous season/as a percentage of maximum points available, ratio of points won at home to points won away from home (Carmichael et al., 2011).

Using results as an isolated outcome measure, however, ignores other critical components of the vision, mission, strategic plan and financial resources of each individual organization, that have been shown to contribute to sporting success. For example, in the EPL, research demonstrates that at club level, player salary spend is the most influential variable on winning a league match, with the statistical likelihood of the home team winning positively related to the home team’s increased expenditure on wages (Carmichael et al., 2011). An increase in the club wage bill relative to the EPL average is related to the increased likelihood of winning a match by 47%, yet the effect is diminished when the top five teams compete against each other (Cox, 2016). Subsequently, in leagues where competitive balance is not promoted through regulating financial structures, teams that are unable to increase expenditure relative to competing teams may identify achievement of promotion, avoidance of relegation, play-off appearances, cup rounds negotiated, number of live television broadcast appearances or qualification for continental competition as objective markers of success.

In addition, teams that invest in their youth academies will use criteria such as player development markers, the number of players from the academy that make first team appearances in their own club, or revenue/trades earned from selling “home-grown” players and the minutes they go on to accrue at a professional level, to define success away from the first team level (Crane, 2017).

Within leagues where competitive balance is carefully regulated, team revenue has a reduced impact. However, different challenges to sustained performance are presented in the form of salary caps, salary floors, distribution of new talent through weighted draft systems and a variety of player contract commitments. Thus, team fortunes follow a more cyclical pattern as strong teams age, decline and younger teams mature and develop into championship contenders (Sheinin, 2018).

Given that this model is dominant in North American sports leagues, such as the NBA, NFL, Major League Baseball (MLB), Major League Soccer (MLS) and National Hockey League (NHL), where a team’s elite league status in guaranteed through the exclusive franchise model, it might actually be within an organisation’s strategy to perform poorly for a number of seasons. This strategy enables a team to accrue high draft picks and build for future success, once a nucleus of talented young players has been assembled. The controversial strategic tactic of “tanking”, where a team actually seeks to finish bottom of the standings, as opposed to languishing mid-table in the hope of scoring higher draft picks, has formed the foundation for success for teams like the 2016 Chicago Cubs and the 2017 Houston Astros in MLB (Sheinin, 2018). In these instances, therefore, success may actually be defined by achieving negative performance metrics and instead the accumulation of high draft picks and salary cap space, as opposed to achieving positive performance metrics in the arena of play.

Whilst this strategic approach can erode a fan base and reduce sponsorship revenue, at least in the short term, embracing the decision and being honest with stakeholders can minimise the impact. The Philadelphia 76ers (NBA) built a brand around the approach and christened it “The Process”, famously selling t-shirts emblazoned with “Trust The Process” on the front, in order to engage stakeholders in the journey (Rappaport, 2017). In early 2018, the New York Rangers (NHL) adopted the same approach and openly divulged their strategy to their stakeholders (Loennecker, 2019).

Knowledge

Given the degree of expertise employed by many HPSOs and the value of the intellectual property they create, the drive to disseminate knowledge and facilitate knowledge sharing is central to some strategies. In 2016, UFC founded the Performance Institute at its headquarters in Las Vegas. Central to the Institute’s mission is the aim of “sharing best practices for performance optimization with athletes and coaches around the world” (UFC, 2018).

In recognising the early evolutionary stage that mixed martial arts is at as a sport, there is an understanding within the organisation, that the performance team have to take a comprehensive approach to asking the right questions and collecting the right data, in order to understand what it takes to prepare and compete at the top level in the sport. The UFC Performance Institute has identified its critical role in becoming a “conduit for sharing information…that serves to elevate global knowledge and educate on ‘best practices’ for the sport of MMA” (UFC, 2018). This form of free dissemination is greatly advantageous for UFC, with the organisation contracting all fighters that compete in its competitions. Subsequently, by enhancing the knowledge of training methods, the expectation is that the competitive standard and longevity of the athletes will increase. Such improvements should consequently enhance the competition and, in turn, benefit the parent organization.

Another HPSO that has positioned itself as a key player in identifying and disseminating sport-specific practices, is FC Barcelona. The club’s fabled academy, La Masia, has a long-founded philosophy of using sport to develop young people, some of whom will go on to represent one of the club’s professional sports teams. The organisation has invested significant resources into developing their youth development programmes. La Masia sees “the education of the player in all of its dynamic complexity, within the context of a culture of learning, involvement and self-criticism geared towards performance” and believes that “the academic and human education of each individual is just as, if not more, important as the sports education”. Subsequently, the club is proactive in holding educational events to share this philosophy and system of education. Indeed, the value of educating its community is further upheld, by providing life and career skills programmes for service providers that interact with the club, as well as for the families of the young players that attend La Masia (FC Barcelona, 2018).

Beyond youth education, FC Barcelona has created BIHUB, a platform that brings together all of the organisation’s projects in research, innovation and training, with the aspiration of becoming the “world’s primary centre of knowledge and sports innovation”, through promoting an open culture of collaboration (FC Barcelona, 2015). BIHUB has become a new revenue stream but links back to the organisation’s strategic plan in identifying that the challenge to continue winning, drives the need to keep up with new developments in the areas of sport collectives, sports performance, sports technology and analysis, health and well-being, fan engagement and big data, smart facilities and social innovation (FC Barcelona, 2018). To this end, the club is building an ecosystem for sports clubs and organisations, sponsors, universities and research centres, start-ups and consolidated companies, investors, sport users, professionals, fans and users. It does this by: supporting scientific research projects, promoting innovation focused on joint development of products and services, providing on-line training for professional development and regulated training with masters and postgraduate qualifications and by organising conferences and congresses(FC Barcelona, 2019).

This approach is mirrored by La Liga rivals, Real Madrid (Real Madrid, 2019a), despite the risk inherent with this model, being that in so freely facilitating the sharing of cutting edge information and practices, the organisation gives away a degree of competitive advantage to its sporting adversaries. However, by providing a market for the educational vehicles, revenue is created that can be reinvested into developing further innovation. Additionally, once inside the system, talent can migrate from department to department, with FC Barcelona citing examples of athletes retraining through internal education courses upon cessation of their playing career and staying within the Club. As such the organisation benefits by constantly being ahead of the competition and retaining employees that are already invested in the vision, values and philosophy of the brand (FC Barcelona, 2019).

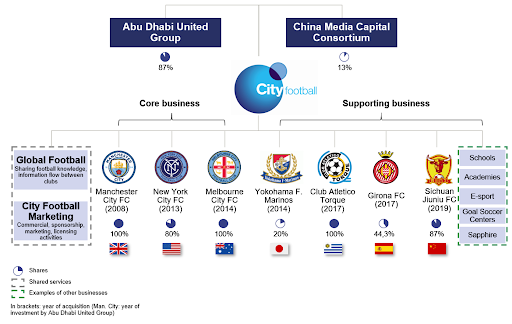

Another model for driving revenue and success through knowledge creation is showcased by City Football Group (CFG), the parent company that owns Manchester City FC. The group also has ownership stakes in Melbourne City FC (Australia), New York City FC (USA), Yokohama F Marinos (Japan), Girona (Spain), Sichuan Jiuniu (China) and Club Atlético Torque (Uruguay) (City Football Group, 2019). Leveraging their internal professional knowledge in science, medicine, marketing, coaching and scouting, CFG shares findings from research and development projects throughout its network but also sells systems to other HPSOs in the industry to generate revenue. The organisation has also collaborated with universities and sports governing bodies to further enhance its knowledge creation and dissemination network (City Football Group, 2018).

A similar model has been developed by Red Bull, who also own football teams such as Red Bull Salzburg (Austria), RB Leipzig (Germany), New York Red Bulls (USA) and Red Bull Brasil (Brazil). Whilst the teams in Austria and Germany have met considerable resistance through fans’ concerns with an erosion of heritage, amongst other gripes, there are definitely many benefits that such a system brings to the table (Norval, 2018).

Red Bull have developed a unified internal culture which ensures its teams share a general vision, footballing philosophy and values system. These promote knowledge sharing and advancing players through internal talent development pathways. To this end, Red Bull teams’ default is togenerally reject big-money, quick-fix transfers, which contribute to avoiding sky-rocketing ticket prices, and instead they prioritise investing time and money into youth development. Their teams are set up to play fast and entertaining football, which has become a hallmark for the entire brand (Norval, 2018).

In such HPSOs, knowledge creation, in the form of research, as well as systems and process development, and its subsequent dissemination throughout identified internal and external end users, are key criteria for evaluation. As such, success in this area can be defined by data outlining the number of research papers published, revenue generated by education courses or system/technology sales and attendances on courses, training programmes or conferences and costs saved by having centralised means of developing systems, processes and people (City Football Group, 2018, 2019).

Social

The most easily referenced marker of an HPSO’s social impact is the number of members and fan clubs it has registered at any one time (Borussia Dortmund, 2019; City Football Group, 2019; FC Barcelona, 2019; Juventus, 2019b; Real Madrid, 2019b). Data points are also easy to collect in relation to the number of people engaged through community outreach programmes and the amount of resources contributed to corporate social responsibility programmes (FC Barcelona, 2019; Juventus, 2019a). However, this corporate social responsibility model views shareholder value and corporate health as unrelated to societal impact, which places such programmes at risk during times of financial struggle (Beal et al., 2017).

Outside of sport, consensus is building in the corporate community, that businesses must consider the impact they have on society in addition to delivering total shareholder return (TSR). Total societal impact (TSI) is a collection of measures and assessments that capture the economic, social and environmental impact of a company’s products, services, operations, core capabilities and activities. Subsequently, there is a recognition that adding this TSI perspective to strategy, drives organisations to leverage their core business to contribute to society. Subsequently, this pursuit of social impact is actually integral to the strategy and value creation of the company, thus positively impacting the TSR over the long term (Eccles, 2017).

Management consultants, Boston Consulting Group, demonstrated a significant positive relationship between a company’s financial performance and non-financial performance, including environmental, social and governance issues, relevant to its sector and strategy (Beal et al., 2017). Whilst the research did not include HPSOs, the group examined the relationship between financial and non-financial performance in retail and business banking, biopharmaceuticals, oil and gas and consumer packaged goods sectors. In each sector, the top performers for combined performance had higher valuation multiples than median performers and achieved higher margins (Beal et al., 2017).

Given the increasing pressure that a range of stakeholders are placing on organisations to play a more active role in addressing social and environmental issues, this approach can actually explore opportunities between the HPSO and its employees, sponsors, investors and fans. Employees are encouraging their employers to have a greater sense of purpose, whilst seeking to become involved in the delivery of societal impact efforts (Eccles, 2017). Sponsors are aware that the perceived fit between themselves, the HPSO and team identification significantly influences their brand equity constructs (Tsordia et al., 2018).

Investors are increasingly focusing on companies’ social and environmental performance, as their view on what constitutes wealth changes. In 2018, socially responsible investing assets in the five major markets (Europe, USA, Japan, Canada and Australasia) accounted for $30.7 trillion, which represented a 34% increase in two years (Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2018) and more than one quarter of total managed assets globally, an increase on the $18 trillion figure reported 2014 (Beal et al., 2017). Fans are increasingly attuned to information related to the social and environmental impact of the brands to which they are loyal, and it would be complacent to suggest that sporting interests are exempt from this sentiment (Beal et al., 2017).

In other industries, strategic plans that incorporate TSI initiatives have been shown to open up new markets, drive innovation, reduce cost and risk in supply chains, strengthen brands and support premium pricing, gain advantages in attracting and retaining talent and become integral parts of the economic and social fabric. TSI-focused companies have also been shown to grow and thrive over the long term, thus supporting sports organisations to achieve sustained success, whilst staying relevant in the face of evolving societal trends (Reeves & Püschel, 2015).

Subsequently, there is a case to suggest that attributing metrics to objectives related to the delivery of environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards, and subsequently auditing them, should form part of HPSOs’ overall measurements of success. Whilst ESG measures are not designed to measure a company’s TSI, this data is currently the best way to quantify a company’s TSI by providing an insight into the largest impact of an organisation - the intrinsic societal value created by its core products or services (Connaker & Madsbjerg, 2019). Some business structures, such as the B Corporation framework, incorporate these standards into their legislation and as such help to align TSI with strategic planning (B Lab, 2018; Clarkson, 1995; Grimes et al., 2018).

Brand

Research conducted to evaluate the impact of brand awareness on the financial success of sports teams in the Bundesliga, concluded that the significance of engaging fans and potential fans was critical in achieving economic success (Bauer et al., 2005). Furthermore, in the USA, merchandise revenues in the NBA, MLB and NHL, were found to be significantly influenced, in a positive manner, by both success from an athletic perspective as well as by positive brand equity (Gladden & Milne, 1999). Similar findings were reported by FutureBrand (2001), when comparing the on-field performance, brand equity and merchandise revenue between an MLB, an NBA and two NFL teams.

It could be argued that the Bundesliga is one of the best leagues in world sport at engaging their fanbase, given that all 36 professional clubs of the Bundesliga and Bundesliga 2 were historically structured as members’ associations and non-profit organizations owned by their members (Norval, 2018). Despite a structural review in response to concerns that German clubs were struggling to compete with teams from other leagues, a 51% majority share must still remain in control of the members’ associations, although creative organisational structures have been employed to circumvent this model and establish a stranglehold on power within certain HPSOs (Norval, 2018; Ward et al., 2013).

Despite the local focus, clubs such as Borussia Dortmund still invest significant resources into increasing brand awareness in Asia and North America, in addition to courting the domestic market (Borussia Dortmund, 2019). This strategy may actually be a direct response to being fan-owned, which prevents access to the magnitude of financial resources enjoyed by HPSOs operating under the single ownership model, such as Manchester City FC or Paris St Germain (Dietl & Franck, 2007; Franck, 2011). Additionally, broadcast revenues received by the Bundesliga are much lower in comparison to the EPL, Spain’s La Liga and Italy’s Serie A (Deloitte, 2019).

Consequently, it is critical that Bundesliga clubs attract significant revenue through leveraging their brand through fan interactions, media services, merchandising and sponsorship, in order to compete at the intercontinental level, despite these shortfalls in revenue through broadcasting and owner investment. In comparison to the other main European soccer leagues, the Bundesliga’s sponsorship and commercial performance is second only to the EPL (Deloitte, 2019).

Meanwhile, another team proactively following a brand globalisation strategy, AS Roma, have received industry plaudits after their English Twitter account achieved an engagement percentage of 290% in June 2018 and later 316% in October 2018. These figures were the highest worldwide interaction percentages of any other soccer team (Rogers, 2018). This medium is being seen by industry experts as a critical way of expanding the club’s international fan base, “Roma, for instance, know they have limited scope in increasing their fanbase in Italy – the vast majority of Italian football fans will already have a club. It’s a different matter abroad, where football fans may have a passing interest in Serie A without supporting a team. Good social content can help them gravitate to a club and potentially even convert into fully-fledged supporters” (Shah, 2018).

Relying on individual components of brand awareness which provide the most easily obtained data points, such as social media metrics, introduces bias. Subsequently, there is a concern that such biases could erroneously influence board and ownership decisions in relation to staff retention or recruitment, in line with fan sentiment. Social media is characterised by immediacy, emotion and reactivity which runs counter to the objectivity, reflection and considered strategic thinking that should inform decision making in sport. An example of this occurred in 2018, when a training ground argument between the then head coach of Manchester United FC, Jose Mourinho, and star player, Paul Pogba, was captured on film and subsequently went viral on social media outlets. Data analytics demonstrated that the fans’ opinion and support of Mourinho’s work had fallen by 38% as a direct result of the event, whilst Pogba’s support had risen significantly in comparison. Commentary articles were suggesting that in the face of such public opinion, combined with recent poor results, the Manchester United board could ignore neither the fans’ displeasure, nor the perceived damage to the global brand of the club and could be persuaded to act decisively to terminate Mourinho’s contract (Shah, 2018). In fact, less than three months following the incident, Mourinho was relieved of his managerial duties at the football club, with media sources referring to the fractious relationship with Pogba as a contributory factor in the Club’s decision to act despite the decision costing an estimated £18 million in contractual compensations (Stone, 2018).

Other models have explored a broader range of organisation-wide opportunities that can be associated with executing a strategy aimed at developing the reach of a team’s brand (Villarejo-Ramos & Martín-Velicia, 2007). These have been aimed at identifying and quantifying the cyclical interaction of brand equity metrics (quality, awareness, loyalty, image) with organisational benefits (broadcast exposure, merchandising, sponsorship, environment, ticket sales), perception, team antecedents (coaching staff, star player, perceived success), company antecedents (reputation, tradition, atmosphere) and market antecedents (coverage, location, competence, fans). This approach allows each component in the cycle to be measured and an objective marker of impact and success evaluated. This model mitigates the threat of HPSOs relying on isolated measures of brand awareness, such as social media statistics, which focus on one major stakeholder (e.g. the fans) over all others (e.g. sponsors, investors, employees) and would, therefore, contribute positively to the overall evaluation of success in brand development for HPSOs (Villarejo-Ramos & Martín-Velicia, 2007).

In order to assess success in brand performance, Brand Finance calculates values of the brands in its research using the Royalty Relief approach - a brand valuation method compliant with industry standards set in ISO 10668 (Brand Finance, 2019).

This method incorporates the Brand Strength Index (calculated using brand investment, brand equity and brand performance metrics, which include stadium capacity, squad size and value, social media presence, on pitch performance, fan satisfaction, fair-play rating, stadium utilisation and revenue), the Brand Royalty Rate (calculated applying Brand Strength Index to an appropriate sector in the royalty range) and Brand Revenues (royalty rate applied to forecast revenues) to define overall Brand Value (Brand Finance, 2018).

Global Business

The issue of global expansion is often a contentious issue for many sports fans. Whilst attracting investors and engaging in lucrative markets around the world can significantly impact the spending power of HPSOs, the excessive commodification and marketisation of sports teams, particularly in the upper echelons of professional sport, have been accused of alienating the traditional fan base that such organisations were built upon and founded to serve (Williams & Hopkins, 2011).

In recent years, pressure from broadcast corporations, foreign owners, league administration and shareholders has seen a significant increase in sport teams playing exhibition or in the case of the NFL, NBA and MLB, even competitive league games thousands of miles from home. Now the most popular sports league in China, the NBA has formed partnerships with some of the country’s biggest tech companies, including a reported $500 million deal with Tencent, which allows WeChat to carry its games and highlights. Subsequently, teams such as the Philadelphia 76ers and the Dallas Mavericks have played pre-season games in Shanghai and Shenzhen, whilst in 2019 the Charlotte Hornets and Milwaukee Bucks played one of their in-season contests in Paris, France. Consequently, the 76ers have hired Mandarin-speaking staff to help distribute media content and see this area of business as a competitive advantage to be explored in enhancing the value of the organisation (Saiidi, 2018).

Meanwhile, the NFL has been playing regular season games in London since 2007, despite the fact that the costs to the league of transporting and accommodating personnel, promoting the games and hiring venues have seen each fixture record a loss on the balance sheet. The league believes that the investment will soon pay handsome dividends, however, as efforts made in building the fan base have achieved high percentages of repeat attendance and sustained levels of interest. It is expected that this will result in a significant return on investment, in the form of increasing media rights and sponsorship values in the coming years, which will justify persisting with the strategy (Panja, 2016).

In recent years, pre-season tours have become platforms for European soccer teams to raise significant revenue, as they build relationships with markets in Asia and North America. “There are millions to be made in appearance money, sponsors are granted special access that is more difficult to accommodate in the season proper, and brand building with long distance or new fans is championed” (Lawrence, 2017). The value of these tours to China, specifically, have been identified by Brand Finance, who report that 57% of all Chinese fans bought club merchandise and 41% purchased a shirt. The spin-off benefit for sponsors is that 42% of Chinese fans bought brands that sponsor their favourite club (Brand Finance, 2018).

The risks of high-profile pre-season strategies, however, have been well publicised. Costs to promoters and host stakeholders are high and, whilst sponsors are sold on the premise that it is an opportunity to reach new markets, there is a risk that given coaches are often reluctant to play their best players and ticket prices are so high, the matches can easily attract bad publicity. Tickets for FC Barcelona’s game versus Real Madrid in Miami in the summer of 2017 cost nearly nine times the cost of admission to the UEFA Champions League Final, which subsequently prompted outrage in the media (Menary, 2017).

One summer later, Jose Mourinho’s public declaration that the quality of Manchester United’s pre-season encounter with rivals Liverpool, watched by over 100,000 American fans in Michigan, was below par and "not something he would pay to see”, prompted similar negative sentiment (Jones, 2018). Subsequently, commentators have been prompted to suggest that unless the fixtures are part of a coherent strategy on the part of the sponsors, there is a risk that the events can feel a bit irrelevant and a cynical way of exploiting overseas fans (Menary, 2017).

Such global exposure has, however, formed the foundation upon which teams have developed portfolios of international commercial partners and created networks of football academies that, not only support talent identification in far flung corners of the world, but also create important revenue streams. At the top end, FC Barcelona have 17 global sponsors, 27 regional sponsors with a total of 44 sponsors spread over 19 countries of the world. Meanwhile, in pursuit of its aim to remain a “global benchmark in sponsorship”, Real Madrid launched up to 1,740 items of content in collaboration with its global partners, which generated almost 3 billion impressions world-wide in the 2018-2019 season (Real Madrid, 2019a). In the same competitive window, City Football Group reported that over 193 million cumulative television viewers tuned in to watch Manchester City play their Premier League fixtures (City Football Group, 2019).

Aside from corporate partnerships, several HPSOs seek to engage directly with their global communities of fans. Barça Academy gives over 45,000 children across 45 permanent schools, in 22 countries and four continents, the opportunity to learn the club’s style of play and values (FC Barcelona, 2018). Real Madrid’s Foundation covers a similar footprint, with 311 football and basketball schools spread over 77 countries on five continents, serving 44,600 children (Real Madrid, 2019a)and Juventus also reach five continents with their network of 110 international camps and academies (Juventus, 2019a).

In addition, the HPSO’s in-house marketing and events departments have become significant sources of revenue, with Barcelona hosting over 400 international events both at home and around the world, including conferences, VIP parties, graduation ceremonies, football tournaments, Legends games, Fan Zones and trade fairs (FC Barcelona, 2018).

Given the overlap between brand development and global business, the impact that these business operations have on the overall value of an organisation and the respective markers of success can be evaluated using similar metrics to the ones outlined by Brand Finance (2018), whilst also accounting for direct revenue amounts achieved originating from overseas sources.

Heritage

The Australian Sports Commission has outlined the key contribution that sporting heritage plays in the success of HPSOs and argues that history has a vital presence in sport, providing benchmarks for future results. They state that if sports organisations don’t retain records, neither can growth be adequately measured, nor success demonstrated (Blood & May, 2018).

By investing in their heritage, HPSOs can benefit from a strong historical identity by:

i) fostering pride, loyalty and inclusion, which assists retention of current members and attraction of new members;

ii) providing a valuable marketing asset to attract support, funding and sponsorship;

iii) inspiring current and future athletes to emulate and exceed past success;

iv) reinforcing the contribution current endeavours have in creating an organisation’s ongoing story;

v) identifying heritage assets and organisational IP that may be commercially explored.

The growing number of sports museums, and their popularity as tourist attractions in their own right, is an indication that the heritage dimension of sport is recognised as an important source of revenue for HPSOs. The Olympic Museum in Lausanne is one of Switzerland’s most visited museums, whilst Old Trafford (Manchester United’s stadium, which houses its own museum) attracts over 250,000 visitors each year and can be compared with some of English Heritage's top visitor attractions (Pinson, 2017). Such facilities provide outlets and engagement opportunities that satisfy public and corporate interests, enhancing, not only the brand value of an organisation, but in some instances, its internal culture by successfully incorporating their rich sporting history in the formation of current values (Wood, 2005). HPSOs that openly celebrate their past triumphs and disasters, whilst successfully fostering ties to their team’s current story include the New Zealand All Blacks, Manchester United FC, Real Madrid, Juventus, Detroit Red Wings and the Boston Red Sox.

Other HPSOs, such as Real Madrid, Manchester City and FC Barcelona have joint ventured with city councils, educational institutions, governing bodies and corporate partners to take their heritage investments still further. Strategies include undertaking gentrification of blighted urban areas in vicinity of their stadia and providing extensive resources for local communities, which include university campus buildings, sports facilities, parks and residential housing (City Football Group, 2019; FC Barcelona, 2018; Real Madrid, 2019a).

Measuring success related to heritage projects can include sphere of influence metrics, footfall data, related membership retention and attraction statistics, asset appreciation, generation of related revenue, in addition to internal employee satisfaction and engagement measures (FC Barcelona, 2018).

Support

Just as with any corporate entity, HPSOs have an array of professions which support their sporting operation. Whilst smaller organisations may have individuals performing a specific professional role, or even outsource certain aspects of operational support, larger organisations will have dedicated departments for sports science and medical services, human resources, planning strategy and innovation, information systems & technology, facility operations, travel, security, compliance and legal (Borussia Dortmund, 2019; Juventus, 2019b; Real Madrid, 2019a). Those teams operating under an umbrella structure that incorporates a number of sister teams, may have a central hub that manages centralised operations such as accounting, corporate partnerships, scouting and information technology (City Football Group, 2019).

In order to identify and construct KPIs that match each individual program’s specific goals and philosophies with effective performance analysis, it is necessary for each department to understand the foundational methodology of data organisation for both objective and subjective metrics. Forming KPIs is an essential aspect of the scientific analysis process and should be done both on an individual and group basis. It is necessary to remain cognisant that the KPIs of one particular department, team, or comparative department between teams, may be totally different than the KPIs from another, as context dictates. However, each set must be configured to optimally serve each institution based upon their needs (Hauck, 2018). In doing so, it is important for departments that may have overlapping jurisdictions, to be cognisant of areas of potential conflict and collaboratively establish clear priorities, so as to prevent ambiguity around intervention that leads to conflict, a lack of accountability and an underlying toxicity.

Each department will structure their respective key performance indicators, aligned to aims and objectives consistent with the strategic plan laid out by the overall organisation. These objectives may be linked to performance measures in other departments, such as coaching and talent identification, or may be more unique to the department according to the nature of the roles and responsibilities of the staff involved (Dijkstra et al., 2014).

Economic

Sports organisations receive revenue from a variety of sources, including media broadcast contracts, sponsorships, merchandise sales, ticket sales, facility rental, events, intellectual property and in certain leagues where players’ contracts are traded for financial recompense, player transfers. In leagues where teams are independent entities, for example the EPL, La Liga, the Bundesliga and Serie A, broadcast revenue is usually shared amongst league members. In leagues where teams are franchised entities issued by the league, for example the NFL, the NBA and MLB, sponsorship contracts, merchandising and ticket sales may also be shared between the franchises (Ejiochi, 2014).

Additionally, sport governing body organisations will receive federal funding and grant awards from both public and private purses, to support aspects of their high-performance programmes. For example, Cycling Canada’s biggest stakeholder is Own the Podium (OTP), which receives much of its support from the federal government, which contributes $62 million in enhanced excellence funding each year through Sport Canada, to support both winter and summer sports. Provincial governments also collaborate with OTP to support projects that align with provincial and national Olympic and Paralympic programs in the areas of sports science and sport medicine, coaching, training and competition. Independent and predominantly privately funded, the Canadian Olympic and Paralympic Committees, deliver resources to support elite athletes and will also support the governing bodies to fund small projects that influence the high-performance programs (Cycling Canada Cyclisme, 2016).

As OTP focusses on leading the development of Canadian sports to achieve sustainable and improved podium performances at the Olympic and Paralympic Games, it prioritises investment strategies by making funding recommendations using an evidenced based, expert driven, targeted and collaborative approach. Consequently, in order to secure the greatest amount of funding from OTP, Cycling Canada concentrates the majority of its efforts in developing the high-performance aspect of the sport. Therefore, for sports governing bodies, the amount of income awarded through grants and government funding can be considered a measure of success (Cycling Canada Cyclisme, 2013).

Organisational expenditure may include costs related to sports operations (player and coaching payroll, contract incentives, signing fees), non-playing or coaching pay roll, operations, travel, taxes, facility acquisition/maintenance/refurbishment, debt financing, hardware leasing, legal and food/beverage. Some leagues stipulate playing salary caps (NFL, NBA, MLS, NHL), playing salary floors (NBA, NFL) or financial regulations that consider sports operation spend in relation to debt, recent break even, equity and employee benefits (FIFA registered leagues) (Carmichael et al., 2011).

The indicators that are routinely used when evaluating financial performance are sales, operating results (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation [EBITDA]), results from operating activities (earnings before interest and taxes [EBIT]), tax liabilities, gross and net debt, equity, net income for the year, cash (including cash equivalents) flows from operating activities, operating working capital, financial working capital (including free cash flow), revenue and net profit/loss for the year. The economic health of an organisation must consider the results year on year, alongside credit risks, market risks and liquidity risks, to give a fundamental barometer of success in these areas (Borussia Dortmund, 2019; Real Madrid, 2019a).

Conclusion

The breadth of operations observed in HPSOs can be surprisingly broad, with indicators of performance being evaluated in many areas. Consequently, it is neither appropriate nor possible to perceive organisational success based solely upon the in-competition results of the most easily recognised representational team or athlete (Borussia Dortmund, 2019; City Football Group, 2019; FC Barcelona, 2019; Juventus, 2019b; Real Madrid, 2019b). Therefore, in acknowledging the relationship between the various interactive components that contribute to the unique structure of many HPSOs, a thorough assessment and evaluation must be conducted on a case by case basis in order to determine the objective markers of success for each.

The intricate, elaborate and entangled nature of the interactions between each component and its respective KPI within the ecosystem, must be acknowledged in the context of high-performance sport, which is an environment that demonstrates continuous volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (Millar et al., 2018). To achieve sustained success in this landscape demands ongoing measurement, assessment and evaluation of each variable, with subsequent change and innovations being managed concurrently. Consequently, leaders need to have a clear understanding of change management and how this relates to each stakeholder, both within and out with the organisation (Cruickshank & Collins, 2012).

References

B Lab. (2018). Benefit Corporations & Certified B Corps. In Benefit Corporation. https://benefitcorp.net/businesses/benefit-corporations-and-certified-b-corps

Barr, S. (2017). How To Set KPIs. In Stacey Barr - The Performance Measurement Specialist. https://www.staceybarr.com/questions/howtosetkpis/

Bauer, H. H., Sauer, N. E., & Schmitt, P. (2005). Customer-based brand equity in the team sport industry: Operationalization and impact on the economic success of sports teams. European Journal of Marketing, 39(5/6), 496–513. http://files/411/Bauer et al. - 2005 - Customer-based brand equity in the team sport indu.pdf

Beal, D., Eccles, R., Hansell, G., Lesser, R., Unnikrishnan, S., Woods, W., & Young, D. (2017). Total Societal Impact: A New Lens for Strategy. In Boston Consulting Group. https://www.bcg.com/en-ca/publications/2017/total-societal-impact-new-lens-strategy.aspx

Blood, G., & May, C. (2018). Australian Sport History. In Clearing House For Sport. https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/knowledge_base/organised_sport/value_of_sport/australian_sport_history

Bof, F. (2006). Stakeholders and team management for sport and social development: the Barcelona FC case. https://www.easm.net/download/2006/e44efb5f262c08c4e3d95e1c504530f9.pdf

Borussia Dortmund. (2019). Annual Report 2019. BVB, Dortmund, Germany. http://files/14/Borussia Dortmund - Annual Report 2019.pdf

Brand Finance. (2019). Football 50 2019. Brand Finance. https://brandfinance.com/images/upload/football_50_free.pdf

Carmichael, F., McHale, I. G., & Thomas, D. (2011). Maintaining market position: Team performance, revenue and wage expenditure in the English Premier League. Bulletin of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8586.2009.00340.x

City Football Group. (2018). Annual Report 2017-2018. City Football Group, Manchester. http://files/28/City Football Group - Annual Report 2017-2018.pdf

City Football Group. (2019). Annual Report 2018-2019. City Football Group, Manchester. https://www.mancity.com/annualreport2019/downloads/mcfc_annual_report.pdf

Clarkson, M. B. E. (1995). A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Performance. The Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.2307/258888

Connaker, A., & Madsbjerg, S. (2019, January). The State of Socially Responsible Investing. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/01/the-state-of-socially-responsible-investing

Cox, A. J. (2016). An economic analysis of spectator demand, club performance and revenue sharing in English Premier League Football[University of Portsmouth]. https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/portal/files/3593400/An_Economic_Analysis_of_Spectator_Demand_Club_Performance_and_Revenue_Sharing_in_English_Premier_League_Football..pdf

Crane, M. (2017). Comparative success of professional football academies in the top five English leagues during the 2016/17 season. Ag-Hera.

Cruickshank, A., & Collins, D. (2012). Change Management: The Case of the Elite Sport Performance Team. Journal of Change Management, 12(2), 209–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2011.632379

Cycling Canada Cyclisme. (2013). Cycling CANADA Cyclisme Strategic Plan 2013-2016.

Cycling Canada Cyclisme. https://www.cyclingcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Executive-Summary-STRATEGIC-PLAN-2013-20162.pdf

Cycling Canada Cyclisme. (2016). Cycling CANADA Cyclisme Annual Report 2016. Cycling Canada Cyclisme. http://www.cyclingcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/CCC-2016-Annual-Report-final.pdf

Deloitte. (2019). Annual Review of Football Finance. Deloitte, Manchester. http://files/8/Deloitte - 2019 - Anual Review of Football Finance.pdf

Dietl, H. M., & Franck, E. (2007). Governance Failure and Financial Crisis in German Football. Journal of Sports Economics, 8(6), 662–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002506297022

Dijkstra, H. P., Pollock, N., Chakraverty, R., & Alonso, J. M. (2014). Managing the health of the elite athlete: a new integrated performance health management and coaching model. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(7), 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-093222

Eccles, B. (2017). Total Societal Impact Is the Key To Improving Total Shareholder Return. In Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bobeccles/2017/10/25/total-societal-impact-is-the-key-to-improving-total-shareholder-return/#4e6864632113

Ejiochi, I. (2014). How the NFL makes the most money of any pro sport. In CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2014/09/04/how-the-nfl-makes-the-most-money-of-any-pro-sport.html

FC Barcelona. (2015). Objectives and Projects of the Strategic Plan 2015 - 2021. FC Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. http://files/24/FC Barcelona - Objectives and Projects of the Strategic Plan 2015.pdf

FC Barcelona. (2018). Annual Reports 2017-2018.

FC Barcelona. (2019). Annual Report 2018-2019. FC Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. http://files/26/FC Barcelona - Annual Report 2018-2019.pdf

Franck, E. (2011). Private Firm, Public Corporation or Member’s Association Governance Structures in European Football.International Journal of Sport Finance, 5, 108–127. http://files/437/Franck - 2011 - Private Firm, Public Corporation or Member’s Assoc.pdf

Friedman, A. L., & Miles, S. (2002). Developing Stakeholder Theory. Journal of Management Studies, 39(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00280

Gladden, J. M., & Milne, G. R. (1999). Examining the importance of brand equity in professional sports. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 8, 21–29.

Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. (2018). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2018. http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/GSIR_Review2018.3.28.pdf

Grimes, M. G., Gehman, J., & Cao, K. (2018). Positively deviant: Identity work through B Corporation certification. Journal of Business Venturing, 33(2), 130–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.12.001

Hatum, A., & Silvestri, L. (2015). What Makes FC Barcelona Such a Successful Business. Harvard Business Review, 2015(June). http://files/442/Hatum and Silvestri - 2015 - What Makes FC Barcelona Such a Successful Business.pdf

Hauck, M. (2018). Foundations of Applied Sports Science: A Starting Point in Sports Performance. In SimpliFaster. https://simplifaster.com/articles/foundations-applied-sports-science/

Hubbard, D. W. C. N.-H. I. (2014). How to measure anything: finding the value of intangibles in business(Third edit). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Jones, A. (2018). EH? Every single Jose Mourinho quote after the defeat to Liverpool suggests he’s losing the plot. In Dream Team. https://www.dreamteamfc.com/c/news-gossip/413520/jose-mourinho-quotes-liverpool/

Juventus. (2019a). 2018/19 Sustainability Report. Juventus, Turin, Italy. http://files/22/Juventus - 201819 Sustainability Report.pdf

Juventus. (2019b). Annual Financial Report at 30 June 2019. Juventus, Turin, Italy. http://files/20/Juventus - Annual Financial Report at 30 June 2019.pdf

Lawrence, A. (2017). Premier League pre-season tours: a feast for fans in far-flung destinations. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/football/2017/jul/11/premier-league-pre-season-tours-fans

Loennecker, J. (2019). New York Rangers: Rebuilding doesn’t always mean tanking. Elite Sports NY. https://elitesportsny.com/2019/03/05/new-york-rangers-rebuilding-doesnt-always-mean-tanking/

Menary, S. (2017). Football’s preseason season is a major money-spinner for some. In National Business. https://www.thenational.ae/business/football-s-preseason-season-is-a-major-money-spinner-for-some-1.616477

Millar, C. C. J. M., Groth, O., & Mahon, J. F. (2018). Management Innovation in a VUCA World: Challenges and Recommendations. California Management Review, 61(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125618805111

Mora, A. (2018). KPIs in sports: performance measurement at its peak. In Performance. https://www.performancemagazine.org/kpis-sports-performance-measurement/

Norval, E. (2018, November). Why Red Bull’s football empire is doing more good than bad in the game. These Football Times. https://thesefootballtimes.co/2018/11/14/why-red-bulls-football-empire-isnt-the-force-of-evil-many-believe-it-to-be/

Panja, T. (2016). NFL games in London sell out every time and still lose money. In Chicago Tribune Sports. https://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/football/ct-nfl-games-in-london-lose-money-20160929-story.html

Pinson, J. (2017). Heritage sporting events: theoretical development and configurations. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 21(2), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2016.1263578

Rappaport, M. (2017). The Definitive History of “Trust the Process.”Bleacher Report. https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2729018-the-definitive-history-of-trust-the-process

Real Madrid. (2019a). Annual Report 2019. Real Madrid, Madrid, Spain. http://files/18/Real Madrid - 2019 - Annual Report 2019.pdf

Real Madrid. (2019b). Management Report 2019. Real Madrid, Madrid, Spain. http://files/16/Real Madrid - 2019 - Management Report 2019.pdf

Reeves, M., & Püschel, L. (2015). Die Another Day: What Leaders Can Do About the Shrinking Life Expectancy of Corporations. In BCG Henderson Institute. https://www.bcg.com/en-ca/publications/2015/strategy-die-another-day-what-leaders-can-do-about-the-shrinking-life-expectancy-of-corporations.aspx

Rogers, P. (2018). Incredible engagement for Roma’s English Twitter account in June. In LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/incredible-engagement-romas-english-twitter-account-june-paul-rogers/

Saiidi, U. (2018). The NBA is China’s most popular sports league. Here’s how it happened. In Yahoo Finance. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/nba-china-apos-most-popular-065300068.html

Shah, S. (2018). How AS Roma won at Football Twitter. In Pulsar. https://www.pulsarplatform.com/blog/2018/how-as-roma-won-at-football-twitter/

Sheinin, D. (2018). No longer sports’ dirty little secret, tanking is on full display and impossible to contain. In Wadhington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/no-longer-sports-dirty-little-secret-tanking-is-on-full-display-and-impossible-to-contain/2018/03/02/9b436f0a-1d96-11e8-b2d9-08e748f892c0_story.html?utm_term=.0044d8d8266e

Stone, S. (2018). Jose Mourinho: Manchester United sack manager. BBC Sport. https://www.bbc.com/sport/football/46603018

Tsordia, C., Papadimitriou, D., & Parganas, P. (2018). The influence of sport sponsorship on brand equity and purchase behavior. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 26(1), 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2017.1374299

UFC. (2018). A Cross-Sectional Performance Analysis and Projection of the UFC Athlete. Volume 1. In 1(Vol. 1). UFC Zuffa, Las Vegas.

Villarejo-Ramos, A. F., & Martín-Velicia, F. A. (2007). A proposed model for measuring the brand equity in sports organizations. EsicMarket, 123, 63–83. http://files/475/Villarejo-Ramos and Martín-Velicia - 2007 - A proposed model for measuring the brand equity in.pdf

Ward, S., Hines, A., Iammert, J., & Scanlon, T. (2013). Mutuality and German Football - an Exemplar of Sustainable Sport Governance Structures? International Business Academy. http://files/477/Ward - 2013 - Mutuality and German Football - an Exemplar of Sus.pdf

Waśkowski, Z. (2015). Collaboration with Stakeholders in Sports Business Industry: Strategies of Marathons Organizers. IMP Conference. https://www.impgroup.org/uploads/papers/8572.pdf

Watson, N., Durbach, I., Hendricks, S., & Stewart, T. (2017). On the validity of team performance indicators in rugby union. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 17(4), 609–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2017.1376998

Williams, J., & Hopkins, S. (2011). ‘Over here’: ‘Americanization’ and the new politics of football club ownership – the case of Liverpool FC. Sport in Society, 14(2), 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2011.546517

Wood, J. (2005). Olympic opportunity: realizing the value of sports heritage for tourism in the UK. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 10(4), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775080600805556

Yang, G., Leicht, A. S., Lago, C., & Gómez, M.-Á. (2018). Key team physical and technical performance indicators indicative of team quality in the soccer Chinese super league. Research in Sports Medicine, 26(2), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2018.1431539

Comments